If you have ever dreamed of earning money from a stellar music career but were concerned you had little talent, don't let that put you off - a man called Alex Mitchell might be able to help.

Mr Mitchell is the founder and boss of a website and app called Boomy, which helps its users create their own songs using artificial intelligence (AI) software that does most of the heavy lifting.

You choose from a number of genres, click on "create song", and the AI will compose one for you in less than 30 seconds. It swiftly picks the track's key, chords and melody. And from there you can then finesse your song.

You can do things such as add or strip-out instruments, change the tempo, adjust the volumes, add echoes, make everything sound brighter or softer, and lay down some vocals.

California-based, Boomy, was launched at the end of 2018, and claims its users around the world have now created almost five million songs.

The Boomy website and app even allows people to submit their tracks to be listed on Spotify and other music streaming sites, and to earn money every time they get played.

While Boomy owns the copyright to each recording, and receives the funds in the first instance, the company says it passes on 80% of the streaming royalties to the person who created the song.

Mr Mitchell adds that more than 10,000 of its users have published over 100,000 songs in total on various streaming services.

"Eighty-five per cent of our users have never made music before," Mr Mitchell tells the BBC. "And now we've got people who were paying their rent, and augmenting their income, with $100 (£74) or $200 a month from Boomy during Covid."

But, how good are these Boomy created songs? It has to be said that they do sound very computer generated. You wouldn't mistake them for a group of people making music using real instruments.

However, using AI to help compose music isn't exactly new: US classical composer, David Cope, developed such a software system back in the 1980s, following some episodes of writer's block.

One day he set it up to write compositions similar to those by Johann Sebastian Bach. Mr Cope then popped out for a sandwich, and returned to find that the computer had composed 5,000 Bach-inspired chorales. These were later released on an album called Bach by Design.

More recently, in 2019, Berlin-based US electronic music composer, Holly Herndon, made an album called Proto in collaboration with an AI system called Spawn that she had co-created. Ms Herndon is an expert in this field, and has a doctorate in music and computing from Stanford University in the US.

Mr Mitchell says that what has changed in recent years is that technological advancements in AI have meant song-writing software has become much cheaper.

So much so that Boomy is able to offer its basic membership package for free. Other AI song creator apps, such as Audoir's SAM, and Melobytes, are also free to use.

While AI composition inevitably grabs the headlines because of its novelty, new tech is continuing to change many other aspects of the wider music industry.

When the City and County of San Francisco imposed strict lockdowns back in 2020, Matthew Shilvock says that keeping an opera company going proved "extremely challenging".

He is general director of the San Francisco Opera, and it could no longer have "two singers, or even a singer and pianist, in the same room".

But when he tried running rehearsals with his performers online, "traditional video conference platforms didn't work", because of the latency, or delays in the audio and video. They were out of sync.

So, Mr Shilvock turned to a platform called Aloha that has been developed by Swedish music tech start-up Elk. It uses algorithms to reduce latencies.

Elk spokesman, Björn Ehler, claims that while video platforms like Zoom, Skype, and Google Meet have a latency of "probably 500 to 600 milliseconds", the Swedish firm has got this down to just 20.

Mr Shilvock says that, when working remotely, Aloha has "allowed me to hear a singer breathe again".

He adds that looking to wider tech to help solve problems is only natural for an opera house with Silicon Valley on its doorstep. "The energy and the drive to find solutions through technology is just so much part of the DNA of this city."

Meanwhile in Paris, Aurélia Azoulay-Guetta says that, as an amateur classical musician, she "realised how painful it is to just carry, store, and travel with a lot of physical sheet music for rehearsals, and how much time we waste".

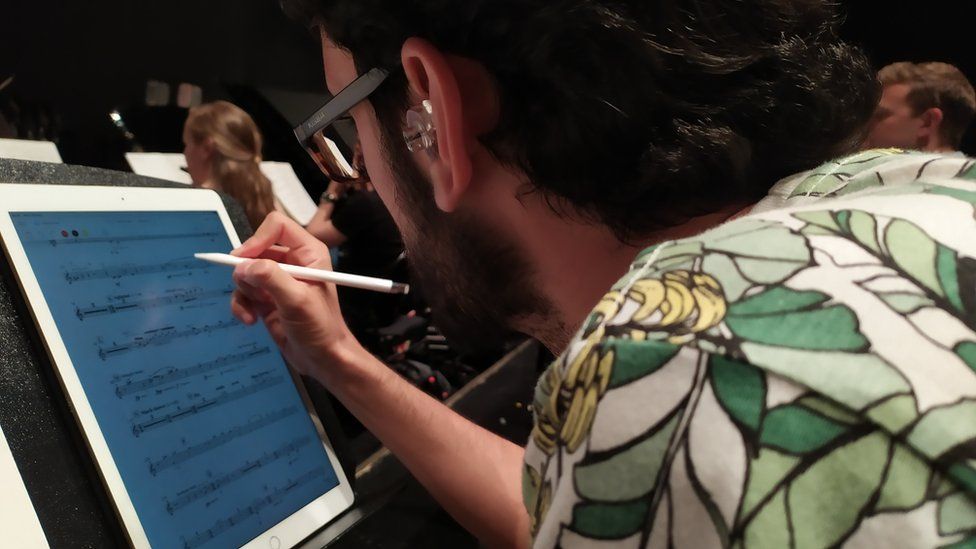

So she and her fellow co-founder "decided to junk our jobs" and launch a start-up called Newzik, which allows music publishers and composers to digitally distribute their sheet music to orchestras.

Ms Azoulay-Guetta says that her solution replaces the stress of musicians having to turn physical, paper pages with their hands during performance or rehearsal. Instead, they now turn a turn a digital page via a connected pedal.

And if the arrangement of a concerto or other composition is tweaked - which can be done by using an electronic pen on the app screen - this will update on every orchestra member's copy of the electronic music sheets.

Ms Azoulay-Guetta says that this feature particularly helped when concerts finally resumed after lockdowns, because orchestras and ensembles faced last minute programme changes - for instance, if musicians were absent, self-isolating.

Other tech firms are focusing on helping musicians more effectively deal with their paperwork. One such company is Portuguese start-up Faniak.

Founder and chief executive, Nuno Moura Santos, describes its app as "like a Google Drive on steroids", allowing musicians - who are often freelancers -to more easily do their admin all in one place, "so they can spend more time writing and playing music".

Back at Boomy, Mr Mitchell is himself a classically-trained violinist. He says that the firm's users are now popping-up everywhere.

"We have Uber drivers creating albums and playing them during their drives," he says. "And [last year] I woke up to a frantic call from my head of engineers, asking if we were under attack.

"There was tons of traffic from Turkey, and we don't have a Turkish version. It was just a YouTuber in Turkey, who did a video about Boomy, and [from that] we have tens of thousands of users there."